During our now bygone holidays I read a little. My present reading artery relates to an idea I call “rural renewal”—the transformation of rural communities through Gospel-preaching, disciple-making work.

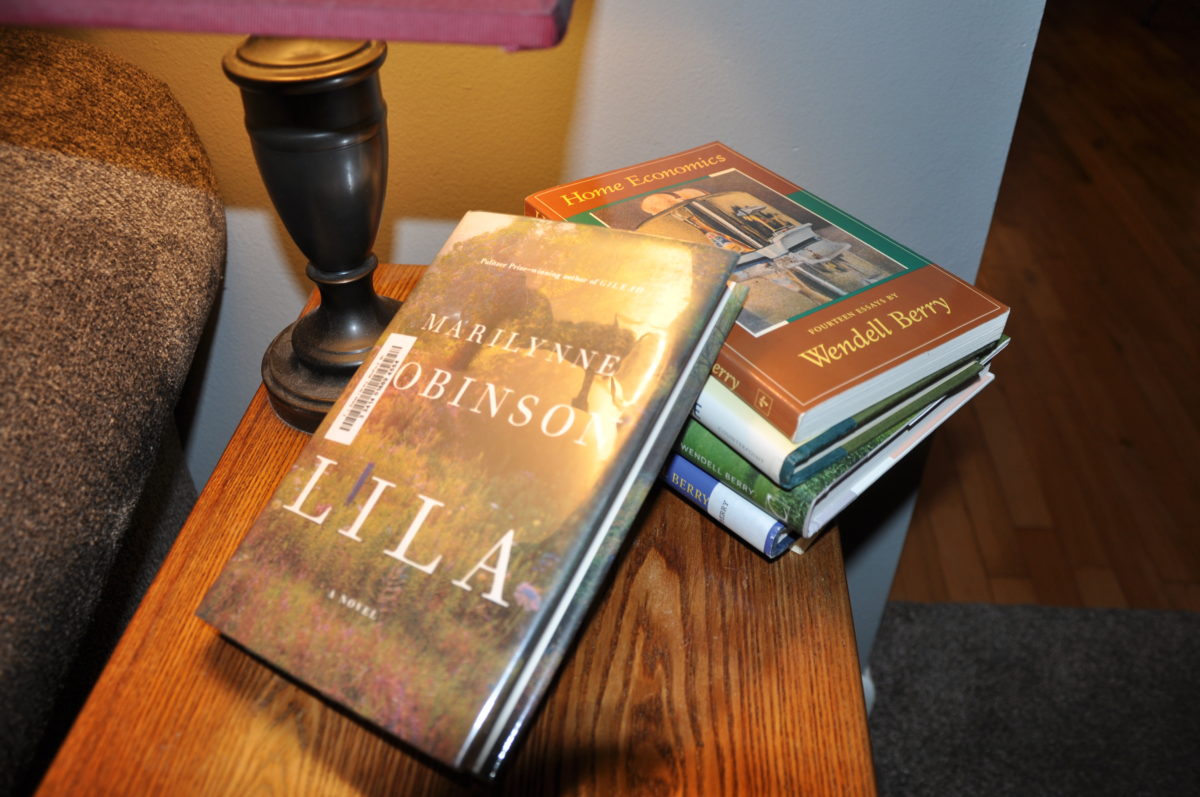

There’s precious little written here. But, from what exists, my favorite by far is actually fiction, a trilogy of fairly recent novels by the Iowa writer Marilynne Robinson: Gilead, Home, and Lila.

Robinson’s literary landscape involves the fictional Iowa town of Gilead—in 1950s Iowa, the northwest region (my guess). John Ames, her central figure, is an aging congregationalist minister who, defying every convention, marries Lila—a deeply troubled former prostitute (though we learn this only gradually, right along with John Ames).

We’ve met Lila before, in the first two novels, and she’s married to Ames at the beginning of Lila, but how she’s come to be the pastor’s wife—after wandering into a church service to “get out of the rain”—becomes apparent only gradually throughout the book.

What I find fascinating is how Robinson, in the figure of Lila, helps me understand the sometimes maddening logic of those who act out of deep hurt. We know them. (Maybe, we are them.) We love them and only wish we could understand them better. These are those who come to our congregations seeking to be anonymous. Serve them, care for them, draw them to the center, and they bolt and are gone. Lila helps us understand why.

Lila’s early life, only a vague shadow of memory to her, involved a dysfunctional family of birth that ostracized her by leaving her on the family porch, for days on end. During one of these periods of rejection, she’s snatched up by Doll, a member of a wandering, hobo community. Doll is a strong, maternal figure who takes Lila to herself like a chick to a mother hen and comes to represent to Lila everything solid and real Lila will search for the rest of her life. Later in the novel, Lila describes the Doll “feeling”,

She wanted to rest her head on a bosom more Doll than Doll herself, to feel trust rise up in her like that sweet old surprise of being carried off in strong arms, wrapped in a gentleness warn all soft and perfect.

Lila eventually finds herself alone after Doll commits murder with a “wicked, old knife” that Lila inherits and keeps under skirt. After a coterie of odd jobs over many years, Lila runs and comes to live in an abandoned shack outside the town of Gilead. There, in the lengthening shadows of the twilight each evening, Lila copies biblical passages from a Bible she’s stolen in her travels. Her favorite passage she finds in Ezekiel where Israel is described as an abandoned child the Lord has taken in, Then washed I thee with water; yea, I thoroughly washed away thy blood from thee, and I anointed thee with oil.

Lila wants to be that baby. And, when she meets John Ames, she does, so to speak. To that point the only constant in Lila’s life has been running. And, even after Lila meets, marries, and comes to learn that she is expecting Ames’ child, Lila is planning to, all of a sudden, walk out the front door. Her maddening logic takes on a kind of sense as Robinson narrates Lila’s personal history, right up to the critical moment when Lila, having just been baptized by Pastor Ames, reveals to Ames what has been forgiven by God,

“I worked in a whorehouse in St. Louis. A whorehouse. You probably don’t even know what that is. Oh! Why did I say that.” She stepped away from him, and he gathered her back and pressed her head against his shoulder. He said, “Lila Dahl, I just washed you in the waters of regeneration. As far as I’m concerned, you’re a newborn babe. And yes, I do know what a whorehouse is. Though not from personal experience. You’re making sure you can trust me, which is wise. Much better for both of us” (89-90).

And Lila does grow in trust. But, like all of us in life, she’s not completely healed this side of eternity. Even late in the book, newborn baby at her breast, Lila reflects on that residual tension from her former self,

The problem is, she thought, that if someday she opened the front door and there, where the flower gardens and the fence and the gate ought to be, was the old life, the raggedy meadows and pastures and the cornfields and the orchards, she might just set the child on her hip and walk out into it, the buzz and the smell and the damp of it, the breath of it like her own breath, her own sweat. Stepping back into the loneliness, a dreadful thing, like walking into cold water, waiting for the numbness to set in that was the body taking the care it could, so that what you knew you didn’t have to feel (256).

Books like Lila change our mental maps. We could read an instruction manual on how to love those struggling with deep hurt, and it might say “be kind, be patient; don’t judge, listen.” Or, we could read Marilynne Robinson and see our imaginations formed through the character of John Ames as he, haltingly and with uncertainty, loves Lila like Christ loves the church (Ephesians 5.25).

I recommend Lila with a caution. This is literature! You’ll need cold weather, hot drinks, a fire and lots of time to nibble through Robinson’s book. Discuss it with me, if you do. And, enjoy it …

I’ve returned my copy. Why don’t those of you in the area order it in through your Westboro Public Library?

Have a great read, and a great week!